Click here to download the full paper (PDF)

Authored By: Dr. Anupam Manhas, Associate Professor, Co-Authored By: Ms. Bandna Shekhar, Ph.D Scholar, Department of Law, Humanities and Arts School of Legal Studies and Governance, Career Point University, Hamirpur, Himachal Pradesh,

Click here for Copyright Policy.

ABSTRACT:

“The present study was undertaken to find out the awareness and exercise of socio-legal rights among the people of the society. Accordingly, a questionnaire was formed with rating-based questions and supplied to all the stakeholders as per selected sample size 318 and the data analysis thereto from Solan, Shimla and Kangra districts of Himachal Pradesh was selected by used simple random sampling technique. Under the study of socio-legal rights of women, it was desirable to have mass opinion of the law experts, academicians, medical attendants, students and public in general so as to complete the study”.

Keywords: Legal Rights, Women’s right, Empowerment.

I. INTRODUCTION:

A ‘woman’ is defined as the “feminine element of the human class” who, separately from helping as a vehicle for fostering human life, is also a creator, a consumer and equally able agent for fostering a wholesome political, social and economic development in society. A women’s right is based on the assumption that all human beings are equal and that the rights which are regarded as natural to another person without any discrimination.

I.I OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY:

One of the main objectives of the study is to find out the awareness among persons regarding the rights of women. To achieve this objective is on the basis by taking opinions from selected representatives of the society who have significant participation or they have substantial exposure to the subject matter and their opinion is likely to provide sufficient insight to the research.

I.I.II HYPOTHESIS:

Most of the individuals are in favor of Women’s rights;

There is misuse of the legal provisions on the part of women;

I.I.III RESEARCH METHODOLOGY:

Sampling Design: Simple random sampling technique.

Universe of Study: law experts, academicians, medical attendants, students and public in general so as to complete the study.

I.II RESULTS AND INTERPRETATION:

From Table 1.1 to Table 1.14 through depicts how the respondents has responded to the questions as per their understanding and perception about the women in the society.

I.II.I GENDER:

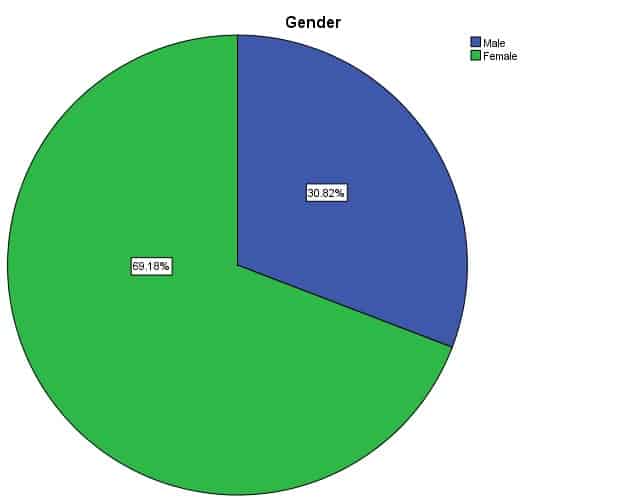

In order to understand the if there exist any opinion variation with respect to the gender of the respondent, the respondents were asked to furnish their gender data. Table 1.1 shows the gender distribution of the sample used for this purpose. In the sample it is clear that, the sample is dominated by females as they make 69% (approx.) of the data whereas the sample contains 31% (approx.) of male respondents.

| Table 1.1 Gender: | |||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Valid | Male | 98 | 30.8 | 30.8 | 30.8 |

| Female | 220 | 69.2 | 69.2 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 318 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

I.II.III OCCUPATION:

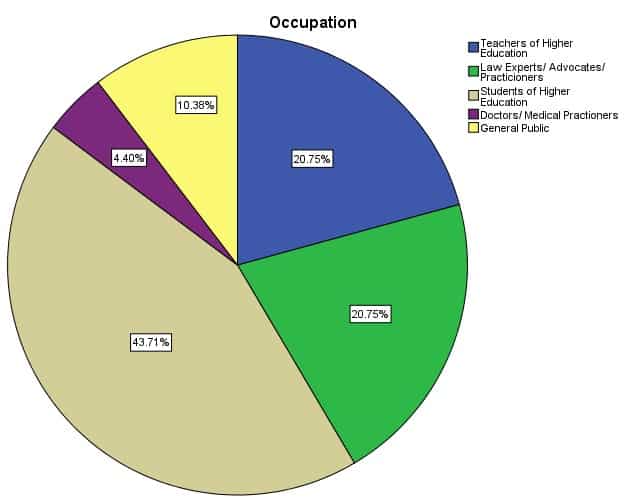

Respondent’s occupation is found to play crucial role in developing understanding and having opinion about a subject matter as the occupation tends to affect the view point of the individual. Thus, to understand the distribution of opinion across various profession of the respondents, the respondents were asked to furnish what their occupation is. Table 1.2 shows the occupation distribution of the sample used for this purpose. The sample for this study is dominated by Students of Higher Education as they make 44% (approx.) of the data whereas the sample contains 4.4% (approx.) of Doctors/ Medical Practitioners as respondents. Also, the data covers 10.4% of general public’s opinion.

|

Table 1.2 Occupation: |

|||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Valid | Teachers of Higher Education | 66 | 20.8 | 20.8 | 20.8 |

| Law Experts/ Advocates/ Practitioners | 66 | 20.8 | 20.8 | 41.5 | |

| Students of Higher Education | 139 | 43.7 | 43.7 | 85.2 | |

| Doctors/ Medical Practitioners | 14 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 89.6 | |

| General Public | 33 | 10.4 | 10.4 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 318 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

I.II.IV AGE:

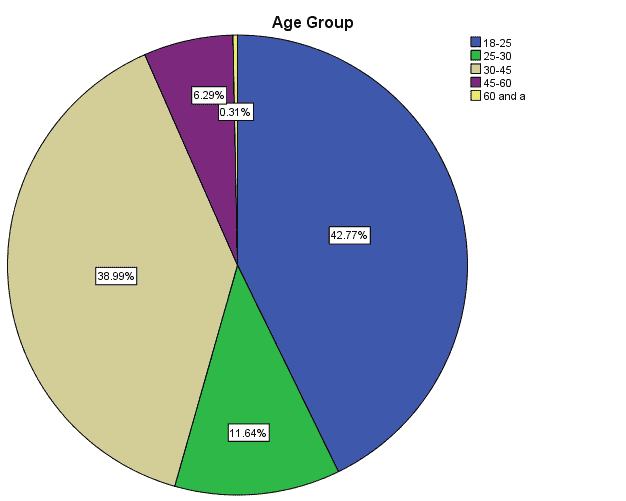

In order to study the association of respondents’ opinion across various age groups the respondents belong, the respondents were asked to furnish their age along with the answers to the questions developed in the questionnaire. Table 1.3 shows the Age-class distribution of the sample used for this purpose. Most of the respondents in the sample for this study fall in the age class of 18-25 years (42.8%) followed by 30-45 years age-class (39%). So combinedly these two age-classes cover more than 80% of the total sample.

| Table 1.3 Age: | |||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Valid | 18-25 | 136 | 42.8 | 42.8 | 42.8 |

| 25-30 | 37 | 11.6 | 11.6 | 54.4 | |

| 30-45 | 124 | 39.0 | 39.0 | 93.4 | |

| 45-60 | 20 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 99.7 | |

| 60 and a | 1 | .3 | .3 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 318 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

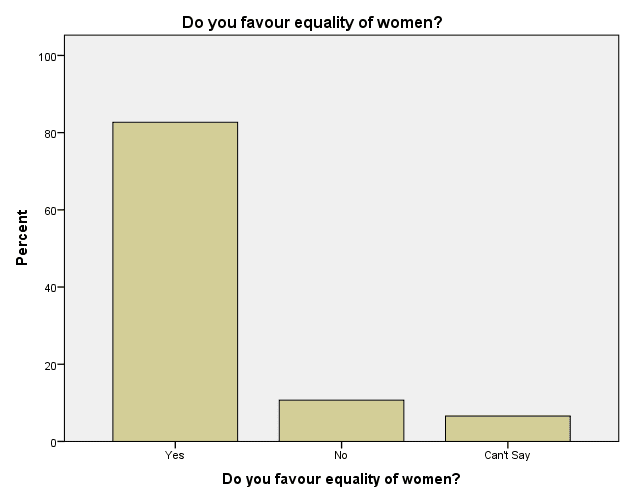

- equality of women?

| Table 1.4 Do you favour equality of women? | |||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Valid | Yes | 263 | 82.7 | 82.7 | 82.7 |

| No | 34 | 10.7 | 10.7 | 93.4 | |

| Can’t Say | 21 | 6.6 | 6.6 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 318 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

After statistical analysis of data through the questionnaire for the above-mentioned question (Table 1.4), all the respondents were found to be of positive opinion that they favor the equality of women.

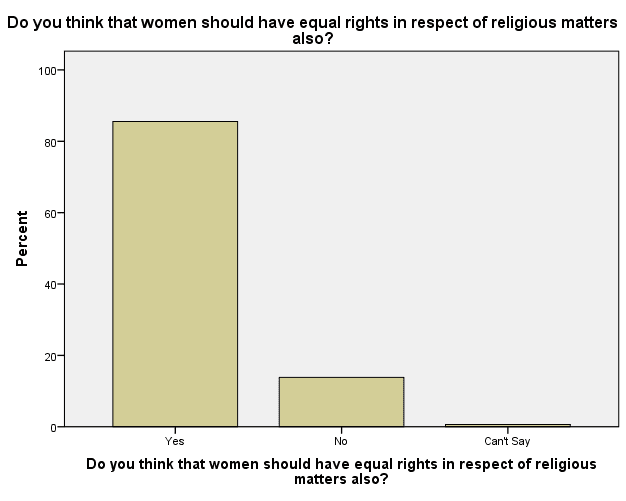

- Women having equal rights in respect of religious matters:

| Table 1.5 Do you think that women should have equal rights in respect of religious matters also? | |||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Valid | Yes | 272 | 85.5 | 85.5 | 85.5 |

| No | 44 | 13.8 | 13.8 | 99.4 | |

| Can’t Say | 2 | .6 | .6 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 318 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

The data revealed (Table 1.5) that all the respondents were of the positive opinion that they women should have equal rights in respect of religious matters.

Certain religious customs in India dictate women’s access terms to place of worship. In the Sabarimala case, the Temple Board had argued and the Kerala High Court also upheld that young women should not offer worship as the temple deity is a Brahmachari (a celibate), for whom women are a source of deviation! In Goolrukh’s case, a Parsi woman was excommunicated from her faith and disallowed entry into the Fire Temple on a self-assumed premise that women ought to take on the religion of their husband, implying that women cannot have their own religious stance! An astonishing thought remains that in these two cited cases, both High Courts gave precedence to the consideration of a religious institution’s rights and a religious custom’s “essential character” over the right to equality and non-discrimination – the rights of women to be treated with dignity and with equal participation in society. In another case of Noorjehan vs. State of Maharashtra, the Bombay High Court, adjudicating a challenge to the ban on women’s entry into the sanctum sanctorum of the Haji Ali Dargah, held that women be allowed unhindered entry into the famous shrine. The Court held that Articles 14, 15 and 25 of the Constitution would come into play once a public character is attached to a place of worship, on which account a religious trust cannot discriminate on the entry of women under the guise of ‘managing the affairs of religion’ under Article 26. The Court, however, did not decide on customs having force of law under Article 13(3)(a), for the simple reason that the respondent itself did not plead the existence of any custom on the basis of which women were denied entry.

Equal rights and dignity of women are subverted in upholding the right of religious institutions, on account of the fact that much importance is given by Courts to the identification of ‘essential practices of religion’. Instead, what is necessary is an effort to identify the customs that are discriminatory and derogatory towards women and hold them in violation of the rights mentioned in our Constitution. This may be done by recognizing customs within the definition of ‘law’ as per Article 13(3)(a) of the Constitution and hence be declared void as per Article 13(1), when found in derogation of Fundamental Rights. It is imperative that courts lay down uniform standards that leave no doubt about the unconstitutionality of discriminatory and regressive religious customs. The stress on Article 26(2) and even Article 25 may be misplaced – Article 13(3)(a) is widely worded to include ordinance, order, bye-law, rule, regulations, notification, custom or usage… within the definition of laws in force. The recognition of religious customs and usages as laws in force will ensure that those in derogation of Fundamental Rights are struck down as per Article 13(1) of the Constitution.

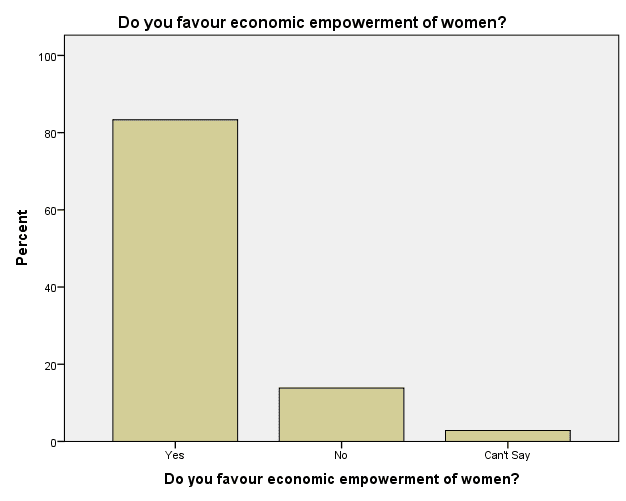

- Economic empowerment of women:

| Table 1.6 Do you favour economic empowerment of women? | |||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Valid | Yes | 265 | 83.3 | 83.3 | 83.3 |

| No | 44 | 13.8 | 13.8 | 97.2 | |

| Can’t Say | 9 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 318 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

The data revealed (Table 1.6) that all the respondents were of the positive opinion that they favor the economic empowerment of women.

Even otherwise also, power empowerment is essential for any nation. The freedom of life of a woman brings enlightening not only the family but also the entire nation. In the modern era, the women are achieving great level in all the fields. They do business, caring family, business, science and technology and what not? Though they earn money, most of them are not empowered economically yet. Earnings of a married women help to lead a family. Mostly middle-class women earnings are contributing more in the family development. But in many occasions, they are not able to take financial decision in their life.

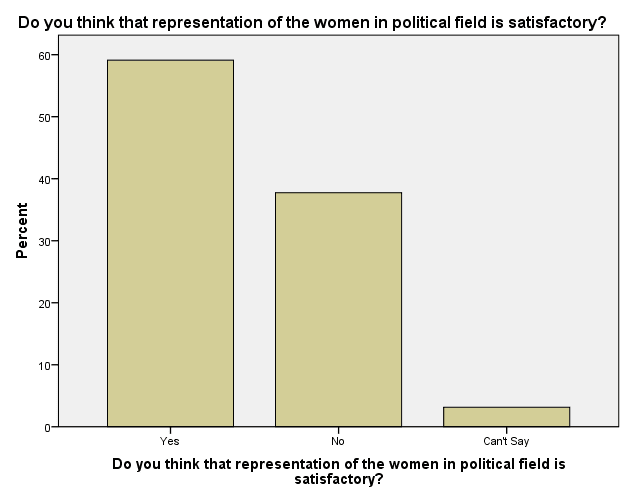

- Women representation in political field:

| Table 1.7 Do you think that representation of the women in political field is satisfactory? | |||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Valid | Yes | 188 | 59.1 | 59.1 | 59.1 |

| No | 120 | 37.7 | 37.7 | 96.9 | |

| Can’t Say | 10 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 318 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

The data revealed (Table 1.7) that majority of respondents were of the positive opinion that the representation of the women in political field is satisfactory. 43 (22.63 per cent) of the respondents especially women denied it and remarked that the women should have adequate representation in proportion to its population whereas 14 (07.37 per cent) respondents responded in the manner that they cannot say.

If we look around the world, we find that women have secured a strong political foothold only in those societies where institutions function according to well-defined democratic norms, where the crime, violence, and overall corruption levels are low, where decision-making is not concentrated in the hands of a few, and where citizens actively participate in local governance without needing to become full-time politicians.

As democracy can become more meaningful only when ordinary women are allowed to take part in political deliberations without having to make heroic sacrifices and prove themselves stronger than men over and over again. However, in the existing circumstances, even talented women cannot stay in politics at their own especially when they are married and have families. They can participate in the public realm only if a supporting family preferably one with a political background is there. Also, the family is having a good amount of surplus money. The staying power of women in politics is also limited due to the fact that while they may get support and even get to be treated as heroines if they win an election, very few women remain politically active once they lose an election. It is perhaps not a coincidence that the few women who have developed an independent political base and are able to compete with men in electoral politics are mostly single or widowed — as for example, Uma Bharti of the BJP, Mamta Banerjee of the Congress Party and Maneka Gandhi of the Janata Dal. These women are able to give their undivided attention to politics because there is no man to hold them back and, therefore, they are not easily cowed down by scandal or character assassination. These three women have had to wage relentless battles within their respective parties for due recognition because their popularity, mass appeal and their organizational skills which are resented by their male colleagues. Yet these women have mostly emerged triumphant because they are celebrities to their supporters. While Indian society may not be very kind to ordinary women, it loves to celebrate women who appear and prove themselves to be stronger than men. In Maneka Gandhi’s case, the aura around the Gandhi family name has played an important role in adding to her charisma, while both Uma Bharti and Mamta Banerjee come from very ordinary families and were not groomed by any powerful patriarchs. Women who show extraordinary resilience, courage and the capacity to withstand character assassination get to be treated with special awe and reverence in our country.

- Women’s representation in local, state and national bodies:

| Table 1.8 Are you in favour of the women’s representation in local, state and national bodies? | |||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Valid | Yes | 241 | 75.8 | 75.8 | 75.8 |

| No | 58 | 18.2 | 18.2 | 94.0 | |

| Can’t Say | 19 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 318 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

After analysis of data collected for the above-mentioned question, a majority of respondents were found (Table 1.8) in the positive opinion that they are in favor of women’s representation in local, state and national bodies. None of the respondents denied about the women’s representation. The rest of 25 respondents responded in the manner that they cannot say.

As a matter of fact, the 73rd and 74th Amendments (1992) to the Indian Constitution have served a major breakthrough towards ensuring women’s access and increased participation in political power structures by mandating one third of elected seats for women at all levels of local government bodies. These amendments have initiated a powerful strategy of affirmative action for providing the structural framework for women’s participation in political decision making and provide an opportunity to bring women to the forefront and center of development and develop new grass root level leadership. However, despite all this, there is still enough scope of strengthening the system and making it perceptive to the needs of the marginalized sections of the society, especially women’s right. It must be admitted that though local governance reforms have enhanced people’s participation in decision making, there are gaps which can be observed when it comes to responding to the needs of women. Women’s issues and concerns like the issues of female infanticide, dowry and child marriage have so far not been addressed in a concrete manner by local governments in India. Secondly, though many women have become a part of local self-governance, they are yet to be seen as capable governance functionaries in their own rights. They are mostly seen as passive beneficiaries of reservations in local governments for women.

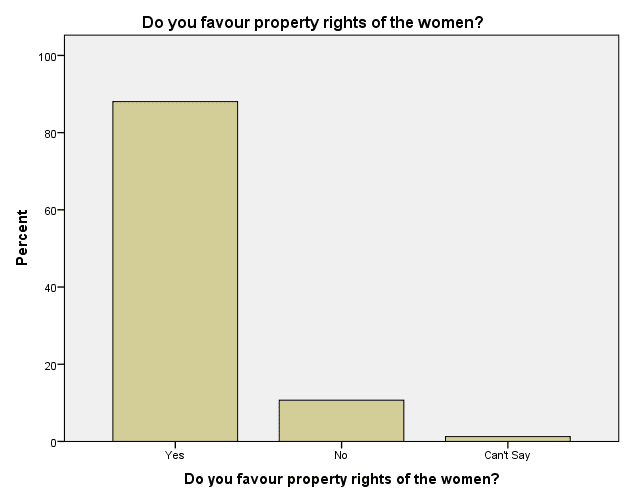

- Property rights of the women:

| Table 1.9 Do you favour property rights of the women? | |||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Valid | Yes | 280 | 88.1 | 88.1 | 88.1 |

| No | 34 | 10.7 | 10.7 | 98.7 | |

| Can’t Say | 4 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 318 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

After analysis of data collected for the above-mentioned (Table 1.9) question, a majority of respondents were found in the positive opinion that they are in favor of women’s representation in local, state and national bodies. 26 of the respondents denied about the property rights in favor of women whereas 20 respondents denied in the manner that they cannot say.

In regard to property rights, Indian women like the women of any other country still continue to get fewer rights in property than the men, both in terms of quality and quantity. What may be slightly different of Indian women is that, along with many other personal rights, in the matter of property rights they themselves are highly divided. Home to diverse religions, India has failed to bring in a uniform civil code. Therefore, every religious community continues to be governed by its respective personal laws in several matters – property rights are one of them. In fact, even within the different religious groups, there are sub-groups and local customs and norms with their respective property rights. Thus Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists and Jains are governed by one code of property rights codified only as recently as the year 1956, while Christians are governed by another code and the Muslims have not codified their property rights, neither the Shias nor the Sunnis. Also, the tribal women of various religions and states continue to be governed for their property rights by the customs and norms of their tribes. To complicate it further, under the Indian Constitution, both the central and the state governments are competent to enact laws on matters of succession and hence the states can, and some have, enacted their own variations of property laws within each personal law. There is therefore no single body of property rights of Indian women. The property rights of the Indian woman get determined depending on which religion and religious school she follows, if she is married or unmarried, which part of the country she comes from, if she is a tribal or non-tribal and so on.

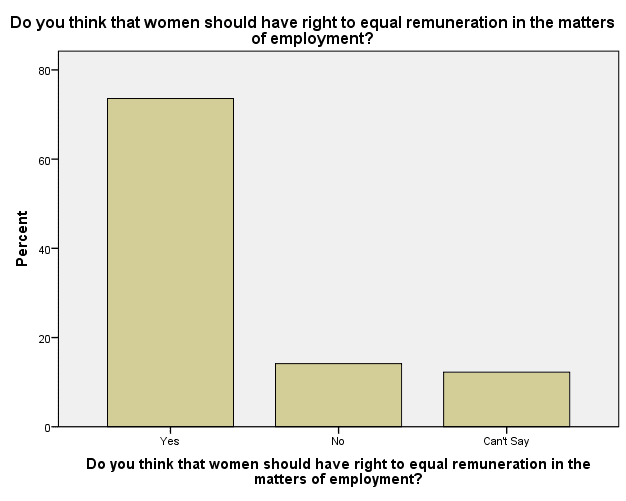

- Women’s right to equal remuneration in employment:

| Table 1.10 Do you think that women should have right to equal remuneration in the matters of employment? | |||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Valid | Yes | 234 | 73.6 | 73.6 | 73.6 |

| No | 45 | 14.2 | 14.2 | 87.7 | |

| Can’t Say | 39 | 12.3 | 12.3 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 318 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

The Indian Constitution has due recognition to the principle of ‘Equal Pay for Equal Work’ for both men and women, and ‘Right to Work’ through Article 39(d) and 41. These Articles are inserted as Directive Principles of State Policy. This means that, they will serve as guidelines to the Central and State governments of India, which are to be kept in mind while framing laws and policies. Efforts have also been employed even on legislative fronts – Equal Remuneration Act, 1976 being the prime one amongst them, Section 4 of which not only emphasizes on equal pay for equal work but even bars the employer from reversing the pay scales in order to attain equilibrium. The principle of Equal Pay for Equal Work was first considered in Kishori Mohanlal Bakshi vs. Union of India[1] in the year 1962 where the Supreme Court declared it incapable of being enforced in the court of law. However, it received due recognition only in 1987 through Mackinnon Mackenzie’s[2] case concerning a claim for equal remuneration for Lady Stenographers and Male Stenographers. This was ruled in favour of lady stenographers as the Court was in favor of equal pay.

Although, times have passed but crisis still remain. The report published by International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) more than a decade ago in March 2009 revealed the existence of gender pay gap to the extent of 30 percent in India in 2008.[3]Agreed that the issue is more rampant in case of gender pay gap especially in private and agriculture sectors where females put the same efforts and time and do the same kind of work as their counterparts.

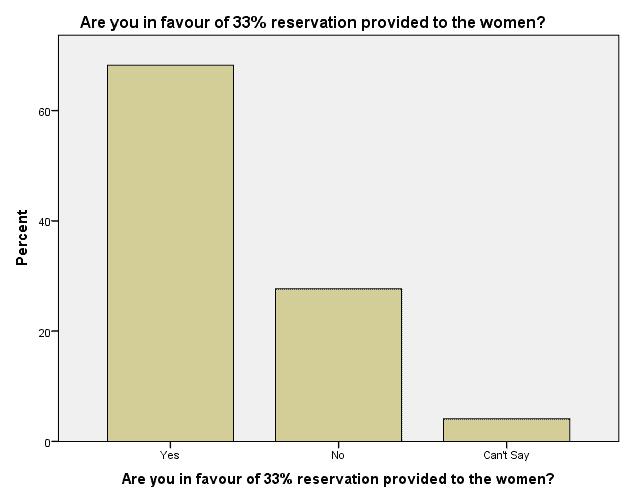

- 33% reservation provided to the women:

| Table 1.11 Are you in favour of 33% reservation provided to the women? | |||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Valid | Yes | 217 | 68.2 | 68.2 | 68.2 |

| No | 88 | 27.7 | 27.7 | 95.9 | |

| Can’t Say | 13 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 318 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

The Women’s Reservation Bill of 2008 or the Constitution 108th amendment concerning 33% reservation of seats for women in the Parliament and in all state legislative assemblies is based upon a constitutional amendment that was passed in 1993 calling for one-third of the council leaders, a Pradhan position in Gram Panchayat to be reserved for women. The bill was passed by the Rajya Sabha in March 2010, but lapsed after the dissolution of 15th Lok Sabha in 2014. While the jury is still out on the actual benefits of any reservation policy for intended beneficiaries, there is widespread consensus that an affirmative action to empower women, politically, does yield desirable results. And there is data to back this belief. With less than 12 per cent representation in Parliament, as compared to a corresponding global average of 22.4 per cent, Indian women trail their counterparts in many parts of the world.

Research published by the United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research in May, 2018, found that Assembly constituencies in India helmed by women representatives show significantly higher economic growth than those under men. Based on data for 4,265 State Assembly constituencies across four election cycles spanning the period 1992-2012, the authors of the study found that women legislators in India enhance economic performance in their constituencies by about 1.8 percentage points per year, more than their male counterparts. The study also noted women’s efficiency in creating vital infrastructure, especially because they are less likely than men to succumb to corruption, temptation for self-promotion and criminal tendencies. These figures are substantiated by another 2017 research study by Guilhem Cassan, University of Namur, Belgium, and Lore Vandewalle, The Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva. Using two data sets collected by the National Council of Applied Economic Research, the 2005-06 edition of the Rural Economic and Demographic Survey (REDS) and the 2011-12 edition of the India Human Development Survey (IHDS), Cassan and Vandewalle document gender norms in variations across castes and how mandated political reservations for women lead to path-breaking changes in their lives.

The REDS data from rural India, which lists respondents’ preferences for public goods such as water, sanitation, roads and electricity, shows that gender quotas enable women to rise to the position of president in gram panchayats — 95.4 per cent of the presidents in gram panchayats reserved for women were female. The IHDS data, on the other hand, provides quantitative evidence of restricted mobility and stricter gender norms among high-caste women, underscoring the need for policy to bring more women into the political mainstream. In an Employment Policy Paper of 2017 on MGNREGA and its impact on women, the ILO, too, highlighted the gender dynamics of affirmative policies. Using both waves of IHDS data (2004-05 and 2011-12), it shows that work provisions under MGNREGA have helped shift social and economic outcomes in favour of rural women engaged in wage labour, thereby contributing to transformative equality.

Coming back to the quota Bill for the economically backward upper castes, unlike gender-based findings, there is no substantive evidence that preferential treatment based on financial status has the desired effects. While assessing the redistributive effects of affirmative action on poverty in 2010, which they claim is the first such study, Aimee Chin and Nishith Prakash of the National Bureau of Economic Research aver that policies aimed at improving socio-economic outcomes for poor sections are not only highly controversial but also inconclusive in indicating any real benefits. “It remains an open question whether affirmative action policies successfully reduce poverty,” they concluded. Significantly, a major roadblock in putting the new quota into effect on the ground could be the legal tangle. In the 1992 Indra Sawhney judgement by the Supreme Court, a majority (six) of the nine judges on the Bench averred that economic criteria cannot be exclusively used for deciding on reservation. The court consequently barred such reservations based on poverty alone, arguing that social and educational backwardness should also be addressed to counter the historic injustice faced by several generations of the country’s population — here again women literally fit the Bill. Irrespective of its eventual denouement and fate on the legal front, it is clear that the drafted quota Bill arguably has little data to support; whereas the long-pending women’s reservation Bill, which is rooted in extensive research, remains the orphan that nobody wants to adopt.

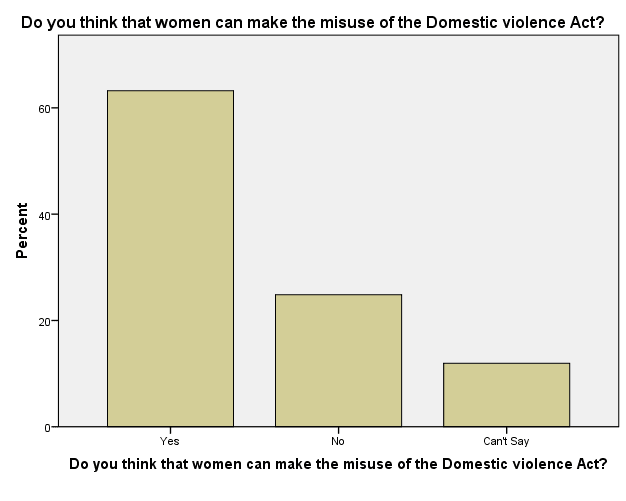

- Women and probable misuse of domestic violence Act:

| Table 1.12 Do you think that women can make the misuse of the Domestic violence Act? | |||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Valid | Yes | 201 | 63.2 | 63.2 | 63.2 |

| No | 79 | 24.8 | 24.8 | 88.1 | |

| Can’t Say | 38 | 11.9 | 11.9 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 318 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

The present data shows (Table 1.12) that majority of the sample respondents feel that the women can misuse the Domestic Violence Act as 63% of the respondents indicate the same against 25% of the respondents.

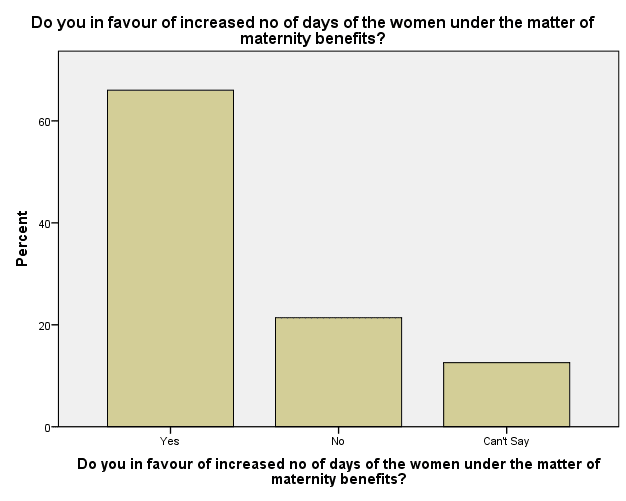

- Days women under the matter of maternity benefits:

| Table 1.13 Do you in favour of increased no of days of the women under the matter of maternity benefits? | |||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Valid | Yes | 210 | 66.0 | 66.0 | 66.0 |

| No | 68 | 21.4 | 21.4 | 87.4 | |

| Can’t Say | 40 | 12.6 | 12.6 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 318 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

The presented data (Table 1.13) shows that majority (66%) of the sample respondents feel that the women should be given more maternity benefits against 25% of the respondents and there are 13% are found to say that they don’t have an opinion on this matter.

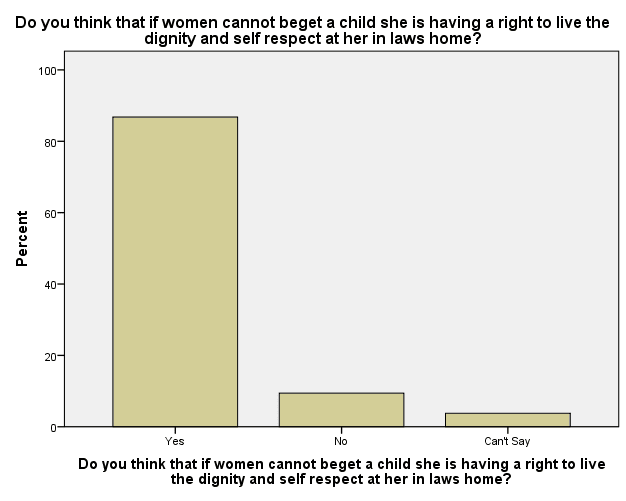

- Right of women without child to live in dignity and self-respect at her in-laws’ home:

| Table 1.14 Do you think that if women cannot beget a child, she is having a right to live the dignity and self-respect at her in laws home? | |||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Valid | Yes | 276 | 86.8 | 86.8 | 86.8 |

| No | 30 | 9.4 | 9.4 | 96.2 | |

| Can’t Say | 12 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 318 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

The present data (Table 1.14) shows that majority (86%) of the sample respondents feel in favour of this against 9.4% of the respondents and there are 3.8% are found to say that they don’t have an opinion on this matter.

II. CONCLUSION:

This is particularly extremely useful to draw the inclination of the society and its various groups regarding the subject matter. This is essential when the concerned party is engaged in the social and economic activities where emotion, physical and psychological throughput are unavoidable and certain control mechanism through law and law enforcement are to play a major role in it. Society can’t have control legally unless all the aspects of the society have been thoroughly studied and understood.

Let’s learn together on Unacademy. Get 10% off on your subscription with my referral code PLUSUZ4R2.

Click on this link to subscribe https://unacademy.onelink.me/u7cm/xwdxv70r.

Cite this article as:

Dr. Anupam Manhas & Ms. Bandna Shekhar, “Socio-Legal Rights of Women: A Study”, Vol.4 & Issue 4, Law Audience Journal (e-ISSN: 2581-6705), Pages 171 to 196 (20th February 2023), available at https://www.lawaudience.com/socio-legal-rights-of-women-a-study/.

Footnotes & References:

[1]Kishori Lal Mohan Lal Bakshi v. Union of India, A.I.R. 1962 S.C. 1139 Retrieved from http://www.companyliquidator.gov.in/12/jud_sc/OFFICIAL%20LIQUIDATOR%20VS.%20DAYANAND.pdfvisited on 10/01/23

[2]Mackinnon Mackenzie and Co. Ltd. vs. Audrey D’Costa and Others (1987) 2 SCC 469Retrieved from http://www.ilo.org/public/english/employment/gems/eeo/law/india/case_law.htmvisited on11/01/23

[3]ITUC Report 2008, Gender (in) equality in the labour market: an overview of global trends and developments Retrieved, 18th July, 2009 from ITUC Report online Retrieved from: http://www.ituc-csi.org/IMG/pdf/GAP-09_EN.pdfvisited on 11/01/23