Click here to download the full paper (PDF)

Authored By: Ms. Ritupriya Gurtoo, Assistant Professor, School of Law, Narsee Monjee Institute of Management and Studies, Indore,

Click here for Copyright Policy.

ABSTRACT:

“Climate change has a wider impact on those sections of the population worldwide that are most reliant on natural resources for their livelihoods or who have the least capacity to respond to natural hazards, such as droughts, landslides, floods and hurricanes. Women commonly faces the higher risks and greater burdens from the impacts of climate change in situations of poverty, as they are often side-line in policy making decisions. Women’s unequal participation in decision-making processes and labour markets compound inequalities and often prevent women from contributing to climate-related planning, policy-making and implementation. One cannot deny women have a vital role in response to climate change due to their local knowledge of and leadership qualities. Women’s participation at the political level has resulted in greater responsiveness to citizen’s needs. At the local level, women’s inclusion at the leadership level has led to improved outcomes of climate related projects and policies.

On the contrary, if policies or projects are implemented without women’s meaningful participation it can increase existing inequalities and decrease effectiveness. State parties to the International conventions have recognized the importance of involving women and men equally in the development and implementation of national climate policies that are gender-responsive. This research paper shall explore the intersection of gender equality and climate change, with a focus on gender-responsive climate policies. The paper will examine the gendered impacts of climate change, and how gender inequalities can exacerbate vulnerability to climate risks. It shall also analyse the role of women in climate action, and the importance of gender-sensitive policies and programs in promoting climate resilience”.

Keywords: Gender Responsive Climate Policies, Climate Risk, Gender Inequality, and International Conventions.

I. INTRODUCTION:

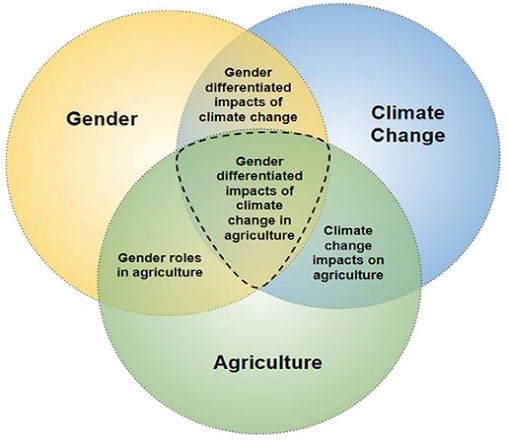

Gender integration across national policy processes is critical to ensure effective implementation of climate change adaptation interventions in agriculture. Gender gaps is often seen in access to information, technologies, markets, and labor burden. Necessity is to address the inter-related issues of gender and climate change instead of looking at them in isolation. Gender integration plays a crucial role in addressing climate policies and promoting climate resilience. It recognizes that gender norms, roles, and power dynamics intersect with climate change impacts and responses. Climate change affects men and women differently due to their distinct roles, responsibilities, and access to resources. For example, in many societies, women are disproportionately affected by climate change because they often have limited access to land, resources, education, and decision-making power. Understanding these gender-differentiated impacts is essential for designing effective climate policies and resilience strategies. Integrating a gender perspective in climate policies involves considering the specific needs, priorities, and capacities of women and men. This requires collecting gender-disaggregated data, conducting gender analyses, and engaging women and men in decision-making processes. Gender-responsive policies aim to address existing gender inequalities and empower women in adapting to and mitigating climate change. Furthermore, Promoting women’s participation and leadership in climate action is crucial for effective and sustainable outcomes. Women’s perspectives and knowledge are valuable in designing climate policies and resilience strategies because they often have deep connections to their communities and possess traditional ecological knowledge. Including women in decision-making processes helps ensure that their voices are heard and their needs are addressed. Gender integration involves building the capacity of women and girls to actively participate in climate-related activities. This includes providing access to education, training, resources, and technology. Empowering women economically and socially enhances their resilience to climate change and enables them to contribute effectively to climate action.

II. OBJECTIVES OF THE PAPER:

- To explore the intersection of gender equality and climate change.

- To examine the gendered impacts of climate change especially in agricultural activities and allied sectors.

- To evaluate challenges of gender-responsive climate policies in agricultural and allied sectors.

- To analyse the role of women in climate action, and the importance of gender-sensitive policies in promoting climate resilience in agricultural and allied sectors.

Climate change mitigation deals with actions that are designed to reduce or prevent emissions of GHG causing human-induced climate change. Mitigation of climate change can be attained by harnessing new technologies, promoting renewable energies, improving efficiency of older energy systems, or changing management practices or consumer behavior. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2014a, 2014b), Mitigation of climate change is delineated as “a human intervention to reduce the sources or enhance the sinks of Green House Gases”. As per the UNFCCC guidelines and requirements, several countries have developed climate change adaptation strategies and programs such as National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA), National Climate Change Policies and Frameworks and Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) highlight the processes through which the countries aim to achieve their national commitments related to climate change adaptation and mitigation in agriculture and allied sectors. Adaptation and mitigation to climate change forms an essential part of these commitments and involves various stakeholders including national, regional, and local level government bodies as well as the private sector. In countries where women play a key role in agriculture production, the extent of gender inclusiveness of these policies can play an essential role in determining the success of adaptation and mitigation actions in agriculture.

III. STEPS UNDERTAKEN AT THE INTERNATIONAL LEVEL:

Tackling the systemic global issue of gender inequality is rooted in international agreements preceding the Paris Agreement: the 1979 United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, the 1995 Beijing Platform for Action, the 2005 Hyogo Framework for Action and the 2015 Sustainable Development Goals, among others[1]. At COP21 and subsequent meeting in 2022 the Convention decided on a ‘shared vision’ for climate action, recognising that ‘gender equality and the effective participation of women are important for climate action on all aspects of climate change’. Importantly, a decade on, stronger climate policies and lower GHG emissions have been found where females have greater representation in national parliaments Various studies have shown that men and women farmers often have different abilities to adapt to climate change, variability, and weather-related shocks, with women in many cases being affected more than men from climate related shocks and stresses[2]. This has been attributed to women’s limited access to timely weather forecast information; limited available options for crop and livelihood diversification; lack of independent source of income, access to credit or financial institutions for better investment; and low decision-making power to apply adaptation measures. Agriculture employs around 60% of the women. Women contribute significantly to agricultural production in activities ranging from cropland preparation and sowing to harvesting, livestock management, and post-harvest activities.[3] Their considerable involvement highlights the need to address the gender gap in terms of access to resources, productivity, and vulnerability in agriculture in the wake of climate change. Enabling resource access and building capacity of women farmers can provide positive community outcomes. Strengthening the capacity of women farmers therefore is an essential step toward building resilient farm households, agricultural communities, and food systems.[4]

Fig 1: Conceptual diagram to define the gender-agriculture-climate change nexus

The climate crisis, just like nearly every other humanitarian and development challenge, has a greater impact on women. This is due to the unequal sharing of power between women and men, the gender gap in access to education and employment opportunities, the unpaid care burden, prevalence of gender-based violence, and all other forms of deep-rooted gender-based discrimination. For example, women play a significant role in agricultural production, but often do not have equal access to agricultural resources and services or official decision-making processes concerning agriculture and climate change. According to one estimate, if all women smallholders received equal access to resources, their farm yields would rise by 20 to 30 percent, 100 to 150 million people would no longer go hungry, and carbon dioxide emissions could be reduced by 2.1 gigatons by 2050 through improved farm practices. In addition, involving women in decision-making can help drive the adoption of climate change policies and strengthen mitigation and adaptation efforts by ensuring they benefit the needs of women. But often, women’s participation in decision-making and their climate leadership potential is hindered by their unpaid care responsibilities. Across the world, women carry out more than 75 percent of unpaid care work, or 3.2 times more than men. When climate-induced disasters hit, this figure only increases as women take on additional burdens to help their households and communities recover and rebuild. Climate-induced stressors can also impact access to education and the labour market for women and girls, increasing the time they must spend on household chores and therefore perpetuating a cycle of disempowerment.

Moreover, in the aftermath of climate-induced disasters, women and girls can be more vulnerable to gender-based violence and therefore need access to quality services essential for their safety and recovery, as well as seats at the decision-making table. For example, Bhutan has trained Gender Focal Points within different ministries as well as women’s organizations to enable them to coordinate and implement gender equality and climate change initiatives. Given the barriers and existing inequalities that women face in access to resources, credit, technology, jobs, and economic opportunities, new financing mechanisms can enable women to better contribute to climate action. For example, Zimbabwe is establishing a renewable energy fund that will create specific entrepreneurship opportunities for women. In Uzbekistan, a pilot green mortgage scheme helped rural households in 5 regions access affordable low-carbon energy technologies. Because of the scheme’s gender-responsive criteria and targeting, 67 percent of mortgages were taken out by women-headed households. Increasing the gender-responsiveness of climate finance is a win-win, improving the effectiveness, efficiency, and sustainability of investments while also increasing women’s empowerment and resilience.[5] Countries also need to be accountable about their gender equality progress and outcomes for women and men, and they need to assess how gender-responsive their climate interventions are.

For example, Uruguay has established a gender-responsive monitoring, reporting and verification system to track how Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) programming is supporting gender equality and women’s empowerment. The system was improved and relaunched in 2021. In Cabo Verde, the Institute for Gender Equality and Equity, a supporting agency across numerous sectors, leads on defining specific needs, targets, and indicators related to gender mainstreaming in climate action across all industries and intervention areas. Cambodia’s NDC included gender as a key criterion for prioritizing mitigation and adaptation actions. This led to most NDC priority actions having targets for women’s participation that ranged from 15 to 70 percent. In addition, the NDC goes a step further to suggest gender-responsive approaches that facilitate women’s meaningful participation in specific climate measures and provides indicators to measure this change. As part of the preparation for the proposed Alaoa Multipurpose Dam Project, women in nearby communities expressed their reluctance to freely share their views in front of village chiefs. In response, women-only consultations were held in nine villages, thereby allowing women to speak comfortably about their specific concerns. Several women appreciated being part of the consultation. They have asked to be kept informed about the project and to also continue holding gender-focused group discussions. In addition to the consultations, a survey was designed to elicit additional gender-related information specific to the dam project. The survey provided an additional outlet for stakeholders, both men and women, to share their views if they were not comfortable speaking in a group[6].

IV. GENDER ADAPTATIONS TO PROMOTE SUSTAINABLE FISHING PRACTICES:

Fishing plays an important role in subsistence and livelihoods in the Pacific. Men are mainly involved in deep sea fishing and cleaning fish reserves, while women are involved in collecting aquatic products, fish processing (cleaning, drying, and smoking), as well as shoreline fishing. Women are under-represented in fisheries organizations and management. Increase women’s access to appropriate climate change adaptive fishing-related technologies and extension services. Expand women’s decision-making in sustainable coastal zone management and fisheries groups. Create sustainable and eco-friendly coastal tourism that increases women’s roles from service industry to management.

V. CHALLENGES IN ADDRESSING CLIMATE CHANGE THROUGH LENS OF GENDER:

Gender equality is only vaguely addressed, without specific actions and policies being put forward by most countries. One of the main problems was the lack of gender-disaggregated information and data, during the development of the NDC, which limited the understanding and evidence base of how climate impacts vary between women and men. In addition, the limited participation of women’s groups and other civil society organizations in climate change policy processes has meant that climate action planning is not always gender-responsive. The lack of support countries to translate gender equality intentions into concrete actions and policy.

VI. RECOMMENDATIONS:

- Prioritizing gender in context: Increase capacity building for institutional staff and key sector leaders on the progression from gender neutrality to gender responsiveness. Define and promote women as agents of change and technology solutions providers, rather than only as users.

- Policy integration of gender: Review legal requirements for addressing climate change and gender equality. Increase women’s representation as decisionmakers in key climate-related sectors.

- Institutional co-ordination across gender and climate change: Require climate institutions and gender machineries to collaborate intensively. Use updated tools and management systems to improve co-ordination, including at the subnational and local levels.

- Fast-track curriculum adjustments to accelerate science, technology, engineering and math’s training for women and girls.

- The pace of curricula adjustments to instill gender equality and human rights values as integral to society and a foundation of skills building for the low-carbon transition is too slow. Training staff, updating curricula and the promotion of course and job opportunities need to be ramped up quickly in developing countries, to attract women and girls into climate mitigation and adaptation key sectors that are in receipt of climate finance and private sector investment.

VII. CONCLUSION:

The post-COVID global recovery adds both complexity and opportunity for aligning the climate, sustainable development and green recovery agendas. Social attitudes and behaviour change are a hugely important part of this, along with the global shift to a low-carbon society and economy. Yet technological solutions remain the primary focus to reduce GHGs, with too little attention given to the value of women’s skills and influence, as well as indigenous knowledge for a more natural approach to emissions sequestration and/or balancing of the way humans thrive. Addressing the difference between core societal values and pervading gender-based behaviour, is as critical as integrating gender considerations at all stages of the project cycle and at all levels of the workforce. Gender-responsive climate finance mechanisms consider the specific needs of women and men in resource allocation. This involves ensuring that financial resources reach women, who may face barriers to accessing funding due to gender inequalities. It also involves integrating gender considerations into climate-related budgeting and investment decisions. Overall, gender integration in addressing climate policies and promoting climate resilience recognizes the importance of gender equality and women’s empowerment in tackling the challenges posed by climate change. By considering the diverse experiences, perspectives, and capacities of women and men, we can develop more inclusive, effective, and sustainable solutions to climate change.

Cite this article as:

Ms. Ritupriya Gurtoo, “Gender Integration In Addressing Climate Policies And Promoting Climate Resilience”, Vol.5 & Issue 2, Law Audience Journal (e-ISSN: 2581-6705), Pages 33 to 42 (29th May 2023), available at https://www.lawaudience.com/gender-integration-in-addressing-climate-policies-and-promoting-climate-resilience.

References:

- Acosta, M., van Bommel, S., van Wessel, M., Ampaire, E. L., Jassogne, L., and Feindt, P. H. (2019). Discursive translations of gender mainstreaming norms: The case of agricultural and climate change policies in Uganda. Women Stud. Int. Forum 74, 9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.wsif.2019.02.010

- Ampaire, E., Acosta, M., Kigonya, R., Kyomugisha, S., Muchunguzi, P., and Jassogne, L. (2016). Gender Responsive Policy Formulation and Budgeting

- Beuchelt, T. D., and Badstue, L. (2013). Gender, nutrition-and climate-smart food production: opportunities and trade-offs. Food Sec. 5,709–721. doi: 10.1007/s12571-013-0290-8

- Chaudhury, M., Kristjanson, P., Kyagazze, F., Naab, J. B., and Neelormi, S. (2012). Participatory Gender-Sensitive Approaches for Addressing Key Climate Change Related Research Issues: Evidence From Bangladesh, Ghana, and Uganda. Working Paper 19. Copenhagen: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS).

- Fisher, M., and Carr, E. R. (2015). The influence of gendered roles and responsibilities on the adoption of technologies that mitigate drought risk: the case of drought-tolerant maize seed in eastern Uganda. Glob. Environ. Change 35, 82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.08.009

- Gartaula, H. N., Niehof, N., and Leontine, V. (2010). Feminization of agriculture as an effect of male out-migration: unexpected outcomes from Jhapa District, Eastern Nepal. Int. J. Interdisc. Soc. Sci. 5, 565–577. doi: 10.18848/1833-1882/CGP/v05i02/51588

- Huyer, S. (2016). Closing the gender gap in agriculture. Gender Technol. Dev. 20,105–116. doi: 10.1177/0971852416643872

Footnotes:

[1] OECD (2015), Financing UN Security Council Resolution 1325: Aid in support of gender equality and women’s rights in fragile contexts

[2] OECD (2015), From commitment to action: Priorities for financing gender equality and women’s rights in the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals

[3] Mersha, A. A., and Van Laerhoven, F. (2016). A gender approach to understanding the differentiated impact of barriers to adaptation: responses to climate change in rural. Reg. Environ. Change 16,1701–1713. doi: 10.1007/s10113-015-0921-z

[4] World Bank Group FAO, IFAD. (2015). Gender in Climate-Smart Agriculture: Module 18 for Gender in Agriculture Sourcebook (English). Agriculture global practice. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

[5] Lipper, L., Thornton, P., Campbell, B. M., et al. (2014). Climate smart agriculture for food security. Nat. Clim. Change 4,1068–1072. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2437

[6] Aura, R., Nyasimi, M., Cramer, L., and Thornton, P. (2017). Gender Review of Climate Change Legislative and Policy Frameworks and Strategies in East Africa. CCAFS Working Paper no. 209. Wageningen: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS).