Click here to download the full paper (PDF)

Authored By: Ms. Muskaan Bajaj, Student, K.K. Modi University, Durg, Co-Authored By: Dr. Mohammed Bakhtawar Ahmed, Assistant Professor, K.K. Modi University, Durg,

Click here for Copyright Policy.

ABSTRACT:

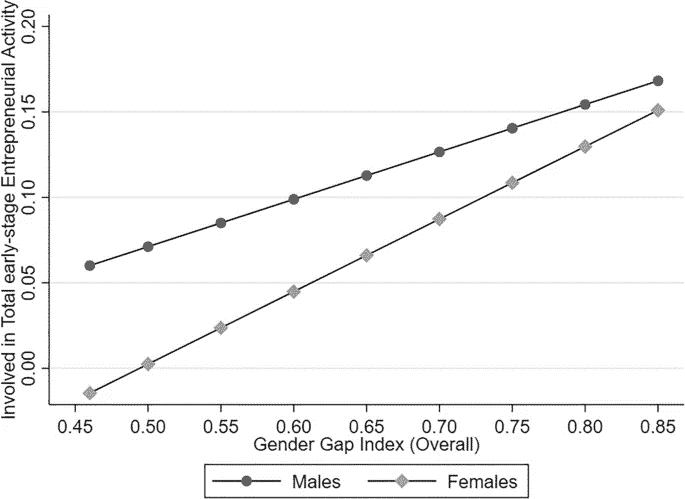

“Notwithstanding the fact that women are less likely than men to launch new businesses, narrowing this gender gap is crucial for promoting long-term economic growth. In this study, we examine whether the gender gap in entrepreneurship is related to gender inequality, as reported at the country level by the World Economic Forum since 2006. When compared to the labor force participation in other sectors, the gap is larger. India’s situation is also not all that different. The role of women in raising families is just one of numerous socioeconomic causes for this discrepancy that may be discovered in research. The Women who own the production components are at a disadvantage due to economics. However, not all gaps can be fully explained by the ownership disadvantage. greater number of business owners Consider entering the service sector since it uses less of the typical production inputs. Considering this, the gender disparity in entrepreneurship is not entirely explicable. This research paper, studies some of the factors involved in enterprise formation and tries to investigate from an attitudinal perspective and tries to differentiate the proclivities of women with respect to men and tries to give a behavioral, attitudinal, psychological explanation to such differences”.

Keywords: Entrepreneurship, Gender gap, Socioeconomic Causes , Gender Inequality.

I. INTRODUCTION:

Any organization or business’s creation is basically social in nature. Yet, it has been discovered that gender still has a significant role in involvement and contribution when starting an enterprise. Males continue to rule the entrepreneurship world. The structural status of women in society or interpersonal differences have been blamed for the gender disparity. In developing nations, 600 million women work in some of the most unstable and unsafe jobs (Hannum et al. 2009; Oxfam 2020). According to research, women are less likely than men to hold top positions, earn less money, own land, and are more adversely impacted by the haphazard application of customary and religious norms in many developing nations (Bertrand et al. 2015; Olanrewaju 2019) With opportunity-driven entrepreneurship as a potential vehicle for the economic empowerment of females, our study highlights the role of policies stimulating gender equality.

II. DATA ON GENDER GAP:

The gender gap and its causes are extensively discussed in the papers from the Kauffman Foundation (2011) and the OECD (2014). India’s situation is not much different either. According to the 4th All India Census of Micro Small and Medium Business (MSME, 2006-07), the percentage of women-owned businesses was just 13.74 percent of the organized sector’s total of 1.56 million units, while it was 7.06 percent of the unorganized sector’s total of 34.612 million. According to recent statistics, women own 7.35 percent of all businesses, both working and non-working (MSME Annual Report, 2014-15). This demonstrates that the percentage of women-owned businesses has not increased much over time. According to complete statistics on entrepreneurship up to 2015, women entrepreneurs in MSME make up roughly 7.8% of all business owners. If self-employment status is considered, both rural and urban women have higher percentages of self-employment. According to the definition of “self-employed,” this includes people who have worked for household businesses. These people are categorized as “own-account workers,” “employers,” and “helpers” at the same time. The individuals are supposed to be working for themselves.

II.I LITERATURE REVIEW:

According to Mitchell (2011), there is an “economic dimension” to women’s entrepreneurship, and nations with lower per capita incomes tend to have larger percentages of female entrepreneurs. The observation is a gender cross-country comparison, however the proportion of female entrepreneurship in a particular setting is lower than that of male entrepreneurship. According to one study (Koehlinger, Minniti, & Schade, 2013), women are less likely to own businesses than males are, rather than failing at starting them more frequently. According to the study, women had lower start-up rates because they have greater levels of failure anxiety, lower levels of self-assurance in their business acumen, and distinct social networks, which together seem to account for the gender discrepancy. Gender disparities in entrepreneurial efficacy have also been researched in addition to motivation. According to a study, women are less likely to launch their own businesses and are better equipped to recognize their own weaknesses (Kourilsky & Walstad, 1998). One could argue that guys are reckless or cling to the idea that ignorance is bliss. Another study on a related topic (Wilson, Kickul, & Marlino, 2007) reveals that the effect of entrepreneurship education on women’s entrepreneurial self-efficacy is greater than its effect on males. Nonetheless, while starting a new business, efficiency is one of the key things that entrepreneurs consider. The study of gender differences and the dominant male characteristics associated with business persons has kept the research challenges open for investigation. Indian gender related socioeconomic context also requires research to identify if any inherent difference influences the choice of entrepreneurship among women. Moreover, gender difference in entrepreneurship is also not a well-researched area in Indian context. In the light of discussion above, this paper investigates gender differences in various processes involved in entrepreneurship.

II.II APPLICATION OF THE STUDY:

The study looks for disparities in the range of variables that affect entrepreneurship between the sexes. In India, women are changing in terms of education, empowerment, the legal system, policy support, and preference in terms of professional options. These changes are anticipated to have an impact on people’s decision to become entrepreneurs, and the study would support this by providing the supporting data.

II.III RESEARCH PURPOSES:

According to the literature evaluation, the current study attempts to investigate the following areas:

where there are few academic publications relevant to India:

- Do men and women view business difficulties differently from one another?

- In their own assessments, do women entrepreneurs have less prior knowledge?

- Do women choose and find their business ideas differently than men?

- Do they plan and evaluate the performance of new businesses differently?

- Is there a gender difference that is substantial enough to distinguish their business?

- Does gender affect the level of satisfaction entrepreneurs experience?

II.IV RESEARCH METHODOLOGY:

The World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Reports include data on gender inequality for each nation (WEF). Since 2006, these statistics have been yearly available and made available to the public by the World Bank. We also obtain data on a nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita and unemployment rate from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators. In our models, these variables serve as the control variables. Data from the publicly available Adult Population Surveys (APSs) of the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor are combined with information at the country level (GEM). The APS is a yearly survey that is given to a sample of at least 2,000 persons who are representative of each participating nation. We utilized survey data for this investigation.

Constructs and Variables

Difficulties in operating a firm:

Efficacy includes the entrepreneurs’ perspective of the overall issues. The possibility of choosing entrepreneurship decreases if the person believes running a business is highly difficult. These perceptions depend on the socioeconomic and cultural setting.

Ideas’ sources and evaluation:

Conceptualizing, choosing, and settling on a business idea to work on is one of the most crucial entrepreneurial procedures. The entrepreneur may obtain the initial idea from a number of sources. The variety of sources and ideas reflects the strength of the concepts. certainty regarding success.

Prior to the actual measurement procedure being laid out and business performance being assessed, a sense of performance or creating a gut feeling about achievement takes place.

II.V ECONOMIC EMPOWERMENT:

For women in developing nations, starting their own business is a realistic method to make money and lessen their disproportionately high rates of unemployment and poverty (Sarfaraz et al. 2014). Della-Giusta and Phillips’ (2006) report that women in the Gambia engaged in entrepreneurial activities to generate essential revenue for themselves and their households lends credence to this line of thinking. In a study from Lebanon, Jamali (2009) shown that the need for money and the amount of economic stagnation at the national level were the primary motivators for women to start new businesses. Additionally, recent evidence supports the association between female entrepreneurship, women’s advancement in both the economic and non-economic spheres, and reductions in overall poverty across developing country contexts (Banerjee 2016; Nukpezah and Blankson 2017).

III. RESULT:

The insignificance is driven by multicollinearity stemming from the inclusion of the four interaction terms in the model, especially the interaction term for the Gender Gap Index (Health and Survival) as there is relatively little variation across countries in the latter variable (cf. Table 1). For this reason, we analyzed model specifications in which we included each subdimension separately. Table 4 in the Appendix shows that in these four models the coefficient for Female is negative and statistically significant except in the model for the Gender Gap Index (Health and Survival). In model specifications with only the Gender Gap Index (Economic Participation and Opportunity), the Gender Gap Index (Educational Attainment), or the Gender Gap Index (Political Empowerment), the regression coefficient for Female is negative and statistically significant. The inferences that can be drawn from this model are the same as the ones we draw based on Model 4 in Table 2.

IV. CONCLUSION:

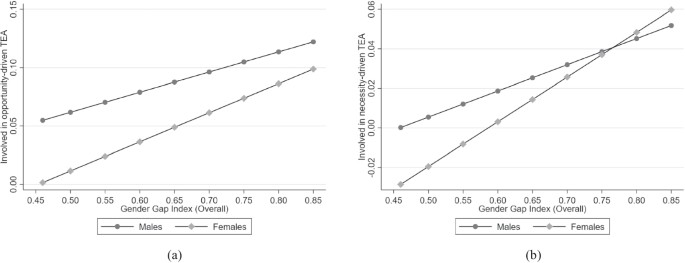

A last argument relates to the more general issue of how “entrepreneurship” is defined by development professionals and academics alike. The economic growth of women-owned businesses continues to dominate the story of entrepreneurial success, ignoring the numerous non-economic contributions made by women entrepreneurs from developing economies (Dean et al. 2019). Economic growth obsession feeds into a patriarchal entrepreneurial standard that makes women entrepreneurs and their businesses look inadequate and underwhelming. We find that better gender equality is also correlated with a reduced gap in opportunity-driven entrepreneurship between males and females when separating opportunity-driven and necessity-driven entrepreneurship. Interestingly, we discover the same for need-driven entrepreneurship—contrary to Hypothesis 2b. Even in the most gender-equal nations, we discover that women are more likely than men to engage in need-driven entrepreneurship. We anticipated that the gender disparity in necessity-driven entrepreneurship would be less in countries with unequal gender distribution due to the relative sensitivity of women’s decision to engage in entrepreneurship to contextual conditions (Estrin and Mickiewicz 2011). The Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations and international policymakers place a strong emphasis on encouraging entrepreneurship to combat poverty (Apostolopoulos et al. 2018) Our findings imply that gender disparity may be a constraint on the poverty alleviation via entrepreneurship, with women driving the multiplier effect by using their business income for family needs.

Cite this article as:

Ms. Muskaan Bajaj & Dr. Mohammed Bakhtawar Ahmed, “Gender Inequality and Entrepreneurial Gender Gap With Special Reference to India”, Vol.5 & Issue 2, Law Audience Journal (e-ISSN: 2581-6705), Pages 136 to 142 (13th June 2023), available at https://www.lawaudience.com/gender-inequality-and-entrepreneurial-gender-gap-with-special-reference-to-india.

References:

- Carter, N. M., Williams, M., & Reynolds, P. D. (1997). Discontinuance among new firms in retail: The influence of initial resources, strategy, and gender. Journal of Business Venturing, 12(2), 125-145.

- Dawson, C., & Henley, A. (2015). Gender, risk, and venture creation intentions. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(2), 501-515. doi: 10.1111/jsbm.12080.

- Gupta, V. K., Goktan, A. B., & Gunay, G. (2014). Gender differences in evaluation of new business opportunity: A stereotype threat perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(2), 273-288.

- Gupta, V. K., Turban, D. B., & Pareek, A. (2013). Differences between men and women in opportunity evaluation as a function of gender stereotypes and stereotype activation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(4), 771-788. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00512.x.