Click here to download the full paper (PDF)

Authored By: Dr. Nguyen Thi Hong Yen, Lecturer of Public International Law, Hanoi Law University (HLU), Vietnam,

Co-Authored By: Ms. Tran Thi Thu Thuy (LL.M), Lecturer of Public International Law, Hanoi Law University (HLU), Vietnam,

Click here for Copyright Policy.

ABSTRACT:

“Outbreak from 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic has become one of the worst health crisis of humankind. As of January 2022, more than 370 million people have been infected with novel coronavirus globally, with deaths exceeding 5.6 million. The Covid-19 outbreak has not been brought under complete control, and it is still lingering in all continents. Therefore, researching and producing vaccines happened to be the soundest measures the countries could take to prevent this virus and bring back the world to the pre-pandemic normal status. However, it is a matter that low-income countries, including Vietnam, are still facing many difficulties when it comes to accessing and administering vaccines to their citizens. This article aims to analyse the issue of equal access to vaccines between countries, thereby pointing out challenges that Vietnam has to face in ensuring the right of Vietnamese people to access the vaccines. Currently, Vietnam is in the top 15 fastest countries that implement universal vaccination, initially overcoming difficulties in accessing vaccines for people[1]. This article will also analyze Vietnam’s strategies to overcome the challenges in vaccinating its people”.

Keywords: Covid-19 Vaccine, Right To Access Vaccine, Human Rights, Equality Right.

I. INTRODUCTION:

CoronaVirus-2019 (2019-nCoV), is a novel virus that causes acute respiratory infections in humans and is highly contagious. This virus was identified during an investigation originated from an extensive seafood and animal market in Wuhan, Hubei province, China. According to data on world meter, by February 5, 2022, there were 391,494,551 cases worldwide, 5,744,061 deaths, and 310,332,614 people cured[2]. Countries worldwide have enforced various measures and policies to prevent the spread of coronavirus, including nationwide lockdowns. However, one of the measures considered to be highly effective, sustainable, and long-lasting is to deploy vaccination for people. Many vaccines have been researched and developed in a short time, but all steps are taken fully and carefully to ensure the effectiveness and safety of the vaccine. After being vaccinated against covid-19, not all are entirely immune from the virus, but it will reduce severe symptoms and mortality if infected[3]. Therefore, countries have poured into researching and developing vaccines and deploying large-scale vaccination campaigns for their citizens. The worldwide vaccination campaigns started to gain momentum around December 2020, with the United States and European countries being the first to administer Covid-19 vaccines. Currently, according to Our world data[4], 4.79 billion people (equivalent to 60.8% of the world population) have received at least one dose of a Covid-19 vaccine. 10 billion doses have been administered globally, and 25.15 million are now administered each day. However, only 9.8% of people have received at least one dose[5]in low-income countries.

It is a fact that most of the vaccines against Covid-19 approved for emergency use in countries today happen to be products of developed countries, such as Pfizer-Biotech, a product of the US and Germany; Moderna is a product of the US; Astrazeneca is a product of the UK and Sweden; Sputnik V is a Russian product; Sinopharm is a product of China. Therefore, developed countries themselves are also those with high vaccination rates. , The rates between high- and low-income countries are highly uneven. In high-income countries, the rate of mass vaccination and complete vaccination is relatively high, usually over 50-60%, such as: in the United Arab Emirates, the vaccination rate is 99% of the population, of which two doses account for 93% of the people; the vaccination rate in China is 88%, of which 85% is given with two doses; in Canada, the rates are 85% and 79% respectively; in Germany 75% and 73%, etc. In contrast, in low-income countries (especially those in Africa), the vaccination rates are very low, usually no more than 20% of the population, such as: in Ethiopia, the vaccination rate is 8%, of which the rate of the people with two doses is 1.4%; in Nigeria, the rates are 6.5% and nearly 2.5%, respectively[6], etc. Thus, access to vaccines between countries is not equal. People in low-income countries have lower access to vaccines than in high-income countries. Therefore, what problems are being faced in low-income countries ensuring people’s right to access vaccines? How should the government solve those difficulties, and how does Vietnam handle this problem?

To address these questions, the authors’ article will cover the following topics: (i) the right to access vaccines and the issue of equality and non-discrimination in international and Vietnamese law; (ii) challenges in ensuring people’s right to access vaccines in Vietnam during the pandemic; and (iii) the strategies that Vietnam has implemented to ensure people’s right to access vaccines during the pandemic.

II. THE RIGHT TO ACCESS VACCINES AND THE ISSUE OF EQUALITY AND NON-DISCRIMINATION IN INTERNATIONAL AND VIETNAMESE LAW:

II.I The right to access vaccines and the issue of equality and non-discrimination under the light of International Law:

The right to health, which has not been adequately addressed before, is a part of the right to an adequate standard of living under Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR, 1948), which states that:

“1. Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing, and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in the circumstances beyond his control.

- Motherhood and childhood are entitled to special care and assistance. Whether born in or out of wedlock, all children shall enjoy the same social protection”.

The provisions of Article 25 of the UDHR were subsequently concretized in Articles 7, 11, 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR, 1966), Articles 10, 12, and 14 of the Convention on the Elimination of all form of discrimination against women (CEDAW, 1979), Article 24 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC, 1989), Article 5 of the International Convention for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (ICERD, 1965). However, Article 12 of ICESCR is considered the most comprehensive international legal provision on the right to health care. According to this Article:

“1. The States Parties to the present Covenant recognize the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.

- The steps to be taken by the States Parties to the present Covenant to achieve the full realization of this right shall include those necessary for:

(a) The provision for the reduction of the stillbirth rate and of infant mortality and for the healthy development of the child;

(b) The improvement of all aspects of environmental and industrial hygiene;

(c) The prevention, treatment, and control of epidemic, endemic, occupational and other diseases;

(d) The creation of conditions that would assure all medical service and medical attention in the event of sickness”.

Regarding Article 12 of ICESCR, the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) explained in a fairly comprehensive and detailed way this right in its General Comment No. 14 adopted at its session 22nd 2002 of the Committee, where the “necessary measures” that the Member States must take to “prevent, treat and limit epidemics” referred to in Article 12(2) include:

- The individual and joint efforts to, inter alia, make available relevant technologies, using and improving epidemiological surveillance and data collection on a disaggregated basis, the implementation or enhancement of immunization programmes and other strategies of infectious disease control

- Establish prevention and education programs for behaviour-related health concerns

- Promoting social determinants of good health, such as environmental safety, education, economic development, and gender equity[7].

It should also be noted that the term “highest attainable standard of physical and mental health” in Article 12(1) refers to an individual’s biological and socioeconomic preconditions and the resources available to an individual of Member States. Many aspects cannot be addressed solely within the relationship between state and individual. States alone cannot guarantee the good health of all citizens, nor can they eliminate all risks to the health of all citizens. Factors such as genetic factors, the individual’s susceptibility to ill health, and the healthy lifestyle and living conditions play an essential role in an individual’s health.

Therefore, the right to health care is understood as the right to enjoy the facilities, goods, services, and conditions necessary to achieve the highest possible standard of health[8]. Therefore, the right to health is understood as the right to enjoy the facilities, goods, services, and conditions necessary to achieve the highest possible standard of health. At the same time, the right to health care depends on the following basic factors: (a) Availability of public healthcare facilities, goods and services, and programs of the member States, (b) Accessibility of all people to healthcare facilities, goods and services.

In the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, CESRC adopted Declaration on the Covid-19 pandemic and economic, social, and cultural rights; accordingly, the Committee recommends that States parties should devote their maximum resources available to the full realization of all economic, social and, cultural rights, including the right to healthcare. The Committee has made clear that the Covid-19 pandemic is a threat to global health and affects the enjoyment of human, economic, cultural, and social rights. To fight the virus as well as coordinate actions to reduce socio-economic impacts and recover effectively, member States have extraterritorial obligations related to the global effort to combat Covid-19, promoting flexibility or other adjustments in terms of existing intellectual property to allow access, disseminating the benefits of scientific advances related to Covid-19 such as diagnostics, drugs, and vaccines[9].

In November 2020, CESCR continued to adopt the Declaration on Universal and Equal Access to Covid-19 Vaccines to make direct recommendations for the distribution and access of Covid-19 vaccines among countries’ members. Accordingly, the Committee considers it necessary to remind the Member States of their obligations under the Convention in this regard to avoid unjustifiable discrimination and inequality in access to the Covid-19 Vaccine. Everyone has the right to the highest attainable physical and mental health standard, including access to “immunization programs against major communicable diseases”. Everyone also has the right to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress, including access to “all the best available applications of scientific progress necessary to enjoy the highest attainable standard of health”. Both rights imply that everyone has the right to use the Covid-19 vaccine, which is safe, effective, and based on the best scientific developments. States are obliged to take all necessary measures, with the leading resources available, to ensure that all people have access to the Covid-19 vaccine without any discrimination[10].

According to the Committee, to ensure vaccine access for all, countries need to:

- Eliminate all discrimination between target groups regardless of any criteria;

- Ensure access to vaccines, especially for disadvantaged groups and people in remote areas. This needs to use both public and private channels through strengthening the capacity of the health system to provide vaccines;

- Ensure affordability or economic access for all, including providing free vaccines;

- Ensure access to relevant information, especially through disseminating accurate scientific information on the safety and effectiveness of various vaccines and public campaigns to protect people from false and misleading information related to vaccines[11].

The Committee has also taken into account the situation where it is not yet possible to have a sufficient quantity of vaccines to be administered to all, where prioritizing access to vaccines by certain groups is inevitable, at least in the early stage, not only at the national level but also at the international level. Under the general prohibition of discrimination, preference must be based on medical needs and public health grounds.

For that matter, preference may be given to healthcare workers and caregivers, or those at risk of developing a more serious health condition if infected with SARS-COV-2 due to age or pre-existing conditions, or those most exposed and vulnerable because of social determinants of health such as those living in informal settlements or other forms of dense or unstable housing, people living in poverty, indigenous peoples, ethnic minorities, migrants, refugees, displaced persons, incarcerated persons, and groups disadvantaged and other disadvantaged populations, etc. In all cases, these priority criteria must be established through a complete public consultation process, be transparent, and be subject to public scrutiny. In a dispute, it must be reviewed to avoid discrimination[12]. The right to non-discrimination, recognition, and equality before the law is considered one of the core principles of international human rights law, regulated directly or indirectly in all international human rights instruments. The most direct are Articles 1, 2, 6, 7, 8 of the 1948 UDHR and Articles 2, 3, 16, and 26 of the ICCPR. In addition, the Human Rights Committee (HRC) also issued General Comment No. 18 on the issue of non-discrimination. Particular attention should be paid to the following issues: Right to non-discrimination, equality before the law, and equal protection of the law shall apply in all situations, including in the case of a state of national emergency covered by Article 4 of the ICCPR; and equality does not mean that one type of treatment applies to everyone in the same situation (i.e. equalization), and not every difference in treatment constitutes discrimination. If differential treatment is determined based on reasonable, objective conditions and to achieve equality, it is not inconsistent with the ICCPR[13].

Thus, in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, based on compliance with the provisions of international law, countries are obliged to ensure health care for people to prevent and control the coronavirus. The Covid-19 vaccine is considered one of the most effective measures to protect people’s health and bring life back to the “new normal”. Therefore, in addition to treating patients with Covid, deploying vaccination is also one of the obligations set for countries. States should ensure that vaccines are accessible to all, without discrimination of any kind. However, the government can identify priority groups to vaccinate first within the country in limited vaccine resources. This differential treatment, which is determined to be reasonable in the national context, is objectively not considered a violation of the principle of non-discrimination. Countries should cooperate to prevent and combat the virus at the international level, and there should be an appropriate sharing and distribution of vaccines among countries.

II.II The Right To Access Vaccines In Vietnamese Law:

The provisions of Vietnam’s law on the prevention and treatment of infectious diseases, the issue of vaccination, and healthcare for people are provided for by the Law on Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases 2007; Law on medical examination and treatment 2009; Law on People’s Health Protection 1989. The first principle mentioned in medical examination and treatment practice is “Equality, fairness, and non-discrimination towards patients”[14].

At the same time, Vietnam has determined the State’s policies on infectious disease prevention and control, including: (1) Priority and support for specialized training in preventive medicine; (2) Prioritize investment in capacity building of staff, monitoring system for infectious disease detection, research and production of vaccines and medical-biological products; (3) Supporting and promoting scientific research, exchanging and training experts, and transferring techniques in infectious disease prevention and control; (4) Support in the treatment and care of people suffering from infectious diseases due to occupational risks and in other necessary cases; (5) Support for the destruction of livestock and poultry carrying infectious agents in accordance with the law; (6) Mobilizing financial, technical and human contributions of the whole society in the prevention and control of infectious diseases; (7) Expand cooperation with international organizations, countries in the region and the world in the prevention and control of infectious diseases[15]. Based on the laws, since the first few cases of covid-19 appeared, Vietnam has made efforts to treat patients. In particular, there are also severe cases, however, Vietnam has been able to successfully treat them, such as the case of patient number 92 – a British pilot[16]. As the number of infections increased, Vietnam quickly established field hospitals and intensive care centres in provinces and cities to treat patients[17].

In addition, during this period, the Ministry of Health of Vietnam has also promptly issued many documents to serve the treatment of people with Covid-19 and implement vaccination activities for people. In the beginning, when the pandemic situation was not too complicated, and the vaccine supply was limited, Vietnam had identified 11 priority groups for vaccination, including medical staff; staff participating in epidemic prevention; diplomatic staff, customs officers, immigration officers; army; police force; teacher; people over 65 years old; groups providing essential services such as aviation, transportation, tourism; people with chronic diseases; people wishing to go on a business trip, study or work abroad; people in epidemic areas according to epidemiological indications, etc[18].

However, from July 2021, when the situation of Covid-19 in the country and internationally became increasingly complicated, and to ensure the progress of vaccination to achieve herd immunity, Vietnam carried out deploying the Covid-19 Vaccine Vaccination Campaign nationwide – the most extensive vaccination campaign in history to inject about 75 million people with 150 million injections were expected in the second half of 2021 and the beginning of 2022[19]. This proved to be an excellent effort by the Government of Vietnam to control and repel the epidemic, protect the health and lives of its people, and ensure that everyone is vaccinated.

III. CHALLENGES IN ENSURING VIETNAMESE PEOPLE’S RIGHT TO ACCESS VACCINES DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC:

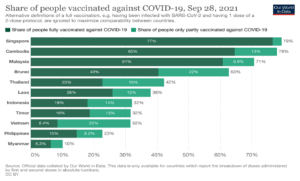

There has been a drastic change in the vaccination rate against COVID-19 for the people in Vietnam. Specifically, as of September 2021, Vietnam had only vaccinated 30.95 million doses of vaccine for people (equivalent to 32% of the population rate); in which 22.66 million people received the first dose of vaccine (corresponding to 23.08% of the population rate) and 8.29 million people were fully vaccinated with both vaccines (corresponding to 8.44% of the population)[20]. At that time, compared to the developed countries and those in the region, the rate was very modest. However, Vietnam has always been aware that vaccines are the most effective way to repel the pandemic and thus used all necessary measures to promote the nationwide vaccination campaign. By the end of 2021, when Vietnam reached 150 million doses of COVID-19 vaccine, 100% of people aged 18 and over had received at least one dose of vaccine, and 90% of people over 18 years of age had received two doses of COVID-19 vaccine. This was considered to be the success of Vietnam in the most extensive vaccination campaign in history. However, to achieve these results, the country also faced many difficulties to ensure that everyone was vaccinated. These challenges come from both domestic as well as international, specifically:

Figure 1: Vaccination rates in Southeast Asian countries as of September 2021[21]:

- At the international level, it is a fact that the distribution of vaccines between developed and underdeveloped countries in the world is uneven. CESCR, in the Statement on affordable universal vaccination against coronavirus disease (COVID-19), international cooperation, and intellectual property, stated: most vaccines have been used and reserved for developed and high-income countries. The Committee further emphasizes that access to a vaccine against COVID-19 that is safe, effective, and based on the best scientific developments is an essential component of everyone’s right to the highest possible standard to achieve physical and mental health along with the right of everyone to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress and its applications. States are therefore obliged to take all necessary measures, as a matter of priority and maximize their available resources, to ensure that all people have access to a vaccine against virus corona without any discrimination. This obligation needs to be realized on a national as well as on an international level because many countries were not able to produce their vaccines. Countries are therefore obliged to cooperate and assist internationally to ensure the accessibility of vaccines against COVID-19, wherever it is needed. The Committee also stated that it regrets the current unhealthy race among States for a COVID-19 vaccine, which created a temporary monopoly of some developed countries on the first vaccine to be produced, particularly in 2021, a critical year for vaccination efforts, as those countries have dominated existing production capacity through public procurement. Due to the global nature of the pandemic, States are obligated to support as much of their available resources as possible in their efforts to provide a vaccine globally. Vaccine nationalism violates the extraterritorial obligations of States to avoid making decisions that limit the ability of other States to give vaccines to their populations and thereby to implement their human rights obligations related to the right to health, as it leads to shortages of vaccines for those most in need in the less developed countries[22].

Underdeveloped countries in general, and Vietnam in particular, face several obstacles in vaccination, influenced by several factors such as healthcare corruption, vaccine nationalism, trade restrictions, vaccine prices, etc[23].

- Corruption in the healthcare sector is a perennial evil everywhere in the world. Worse yet, the COVID-19 pandemic has become a fertile ground for corruption and waste. It opens the door to over-procurement medical equipment such as ventilators, masks, and hand sanitisers without strictly following transparent or public procurement processes. The embezzlement of resources devoted to the health sector, particularly during times of public health emergency, jeopardizes the sustainability of the health system, thereby infringing upon the right of all to receive health care.

- Vaccine nationalism and trade restrictions can be a daunting challenge to equitable access to vaccines. When available, countries will have to jostle for future medical equipment and COVID-19 vaccines to determine their national interests first. Certainly, this is not a new phenomenon. After the H1N1 pandemic, the first world countries secured pre-vaccine doses so large that they outnumbered their populations. Indeed, this lesson has not been well heeded, if at all. Masks and ventilators are likely to reach the highest bidders. After deploying a COVID-19 vaccine, wealthy countries, which account for only 14% of the global population, are hedging once again, stockpiling 53% of the vaccine that could be produced, making continued access to COVID-19 less expensive. Poorer countries’ access to vaccines is much more limited[24]. Therefore, the current distribution of medical equipment and vaccines is commensurate with a country’s purchasing power rather than its public health needs.

- Besides, the price of the vaccine is also one of the factors worth paying attention to. If the price of the vaccine is too high, it will be difficult for middle and low-income countries to access it. And if the vaccine price is reasonable, but the ability to fight the virus is low, it will not bring about high efficiency in practice.

- One of the current barriers for countries to access vaccines is the issue of the protection of intellectual property rights with vaccines. Facing the disaster of the Covid-19 epidemic, on October 2, 2020, India and South Africa submitted to the TRIPS Council a proposal for a temporary exemption from the obligation to protect intellectual property for products and medical technology to respond to the Covid-19 pandemic until the world achieves herd immunity. The obligations proposed to be waived those in section 1 (Copyright and Related Rights), Section 4 (Industrial Designs), Section 5 (Patents), and Section 7 (Protection of Confidential Information) under part II, and the obligation to enforce those sections falls under part III of the TRIPS Agreement. Under this proposal, member countries could suspend intellectual property protection globally for Covid-19-related products, including diagnostic kits, therapeutic drugs, vaccines, and medical equipment needed, everything necessary to prevent the spread of the coronavirus. The Intellectual Property Rights applied in the proposal include copyright, related rights, patent rights, industrial designs, and confidential information. This proposal of India and South Africa received mixed reactions from WTO members with two main streams of opinion: in favour and against. Due to the specificity of the pharmaceutical industry, companies producing brand-name drugs when producing a new vaccine such as the Covid-19 vaccine only really hold a small part of the patents compared to the total number of related patents regarding vaccines. The remaining patents for drug composition will be acquired by vaccine manufacturers for specific components of that vaccine, either from other pharmaceutical companies or researchers. When it comes to the intellectual property of a Covid-19 vaccine, it needs to be more open to all: from licensing agreements to copyrights, to industrial patents, to laws, trade secret protection. The challenge is the legal barrier to the global expansion of Covid-19 vaccine production[25].

The above factors are barriers and challenges faced by Vietnam and middle to low-income countries when they want to have many vaccines to vaccinate people in their countries.

At the national level, to deploy expanded vaccination and achieve herd immunity, Vietnam is facing a number of difficulties such as:

- Vaccine supply is limited. According to the plan, in 2021, Vietnam will receive 120 million vaccine doses through self-negotiation with vaccine manufacturers, national governments, or the COVAX mechanism. However, the vaccine batches are pretty scattered, so vaccination cannot be carried out on a large scale from the start. Vietnam identified the priority groups first. The deployment of new large-scale vaccination has been carried out since the beginning of July until now. Moreover, it is quite challenging to order vaccines now because the production source from pharmaceutical companies is also limited. Besides, due to the re-emergence of the epidemic due to the Delta mutation, the Omicron mutation, countries are considering increasing the booster dose (currently, many countries are deploying the 3rd vaccine injection for people, even Israel has started to inject the 4th dose), which leads to even more scarcity of vaccines.

- Currently, vaccines in Vietnam are given free of charge to the people. The funding to buy vaccines is from the state budget and the contributions and support of domestic and foreign individuals and organizations; sources are voluntarily paid by organizations and individuals using vaccines. According to calculations by the Ministry of Health, it is expected to buy 150 million doses of COVID-19 vaccine to vaccinate about 75 million people, with total funding need estimated at 25.2 trillion VND (nearly 110 million USD), including funding for vaccines, expenses for transportation, preservation, distribution, organization of vaccination[26]. This is the estimated number of Vietnam when administering two injections to people (not including the number of injections for children). However, currently, Vietnam is implementing the 3rd dose injection for people. The country is also carefully studying the vaccination for children aged 5-11, thus needing more funding for the vaccine. Vietnam established a COVID-19 Vaccine Fund with the function of managing and coordinating the Fund’s financial resources for funding activities, supporting the purchase and use of COVID-19 vaccines[27]. As of January 2022, the Fund has received more than VND 8.8 trillion (more than 38 million USD) in donations from domestic and foreign organizations and individuals[28]. However, the implementation of vaccination is a long-term plan. Thus, having stable funding is also one of the central issues warranting the authority’s attention.

- In addition to these, some people hold an “anti-vaccination” mindset sceptical of the effectiveness of vaccines or with a “vaccine selection” mindset, which leads to difficulties in implementing mass vaccination. Besides, people are also afraid of side effects after vaccination. In the beginning, when people did not have a clear understanding of vaccines, some people thought that Pfizer or Moderna vaccines were better than Astrazeneca, so they were hesitant about injecting AstraZeneca. This would cause vaccine scepticism, thus adversely affecting the overall vaccination rate.

IV. EXPERIENCES FROM VIETNAM TO ENSURE PEOPLE’S RIGHT TO ACCESS VACCINES IN PANDEMIC:

Initially belonging to the group of countries with low COVID-19 vaccination rates, with the right and drastic vaccination strategy, Vietnam has become one of the countries with the highest vaccination rates globally, ensuring that all healthy people have the right to get vaccinated. To ensure people’s right to access to vaccines and to fully vaccinate, Vietnam implemented the following decisions:

- The country’s vaccine strategy focuses on importing and transferring technology and research to produce and develop vaccines. When the primary goal has been identified, it will focus on synthesizing many measures to receive as many vaccines as quickly as possible, such as: strengthening partner search, negotiation, diplomacy, and financial mobilization, establishing the COVID-19 vaccine fund. Up until now, Vietnam has also licensed the use of nine vaccines against COVID-19, including AstraZeneca, Sputnik V, Vero Cell, Pfizer/BioNTech, Moderna, Janssen, Hayat-Vax Abdala, and Covaxin. According to statistics from the Ministry of Health of Vietnam, from February 2021 to December 29, 2021, Vietnam received more than 192 million doses of different types of COVID-19 vaccines, of which the state budget bought nearly 97 million doses and also provided aid along with sponsoring more than 95 million doses[29]. Vaccine diplomacy is considered an important strategy to help Vietnam achieve herd immunity.

- Regarding research, technology transfer, and clinical trials of vaccines in the country, the Ministry of Health said vaccine candidates such as Nanocovax, COVIVAC, ARCT-154, HIPRA, Sputnik V, and vaccines made by Shionogi Company (Japan Edition) development. The Ministry of Health is also guiding units in transferring COVID-19 vaccine production technology from other countries such as Cuba, India etc… Also, it has appealed to the World Health Organization to be included in its program for receiving and transferring mRNA technology.

- Simultaneously with receiving batches of COVID-19 vaccines from procurement, support from other countries, and the COVAX mechanism, Vietnam flexibly deployed the distribution of vaccines suitable to each epidemic phase and situation image of each locality. With the 4th outbreak of COVID-19 in Vietnam from April 2021, the period from July 2021 to October 2021 was when the southern provinces had the strongest outbreak with the number of infections in Ho Chi Minh City or Binh Duong, where there were thousands of cases a day. When receiving the vaccine, the Vietnamese government also distributed it equally to the provinces, however, there was priority provided for the cities at the centre of the epidemic. At the same time, the regions and cities also implemented the vaccination quickly at many levels, further implementing the policy of “go to every alley, knock on the door” to “cover the vaccine” as much as possible to the people.

- In addition to preparing enough vaccines to immunize the people, Vietnam also actively carries out propaganda and education activities so that people are fully and accurately aware of the effectiveness of vaccination. The Ministry of Health of Vietnam has cooperated with Meta Corporation to organize the communication campaign “Vaccination – Stay Faithful” to convey a strong message about vaccination against COVID-19 to protect yourself, your family, and the community. This campaign is carried out through Livestream sessions to disseminate knowledge and answer common questions about the disease and how to prevent it through vaccines, thereby raising public awareness about Vietnam’s strategy for vaccination against COVID-19. This campaign has contributed to calling for the consensus and trust of the entire population in vaccination activities, helping Vietnam to achieve herd immunity soon.

V. CONCLUSION:

The right to access vaccines is one of the fundamental rights in the group of health rights that every citizen is entitled to. Despite being in a group of developing countries facing many economic difficulties caused by the pandemic, the Vietnamese state still puts the task of protecting people’s health first.

Therefore, Vietnam has taken all necessary measures to access vaccines quickly and in the best way. The difficulties Vietnam has been facing and is facing are also what less developed countries are facing. Other countries can therefore rely on experiences from Vietnam and apply flexibility to their circumstances to come up with appropriate policies to ensure people’s right to access vaccines, to be able to reach herd immunity, repel the pandemic and establish a new normal.

References:

- Binh Thai, Noon 20/9: Vietnam receives about 50 million doses of covid-19 vaccine: many provinces add new F0s (Trưa 20/9: Việt Nam tiếpnhậnkhoảng 50 triệuliều vaccine covid-19: nhiềutỉnhthêmcác F0 mới), MINISTRY OF HEALTH PORTAL (January.4, 2021, 04:20 PM), https://moh.gov.vn/tin-tong-hop/-/asset_publisher/k206Q9qkZOqn/content/trua-20-9-viet-nam-tiep-nhan-khoang-50-trieu-lieu-vaccine-covid-19-nhieu-tinh-them-cac-f0-moi.

- Binh Thai, Who are the 11 groups of subjects who are vaccinated against COVID-19 in Vietnam? (11 nhómđốitượngđượctiêmvắcxinphòng COVID-19 tại Việt Nam gồmnhững ai?, PORTAL OF THE MINISTRY OF HEALTH ABOUT COVID-19 PANDEMIC (December. 25, 2021, 11:15 AM),https://ncov.moh.gov.vn/en/-/6847426-1677.

- BT, Vietnam’s success in the biggest vaccination campaign in history (Thành côngcủa Việt Nam trongchiếndịchtiêmchủnglớnnhấtlịchsử), SOCIALIS REPUBLIC OF VIET NAM, GOVERNMENT NEWS (January. 5 2022, 04:05 PM), https://baochinhphu.vn/thanh-cong-cua-viet-nam-trong-chien-dich-tiem-chung-lon-nhat-lich-su-102306509.htm.

- CESCR, General Comment No. 14: The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health (Art. 12), E/C.12/2000/4, para.16, https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/4538838d0.pdf.

- CESCR, Statement on the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic and economic, social and cultural rights, E/C.12/2021/1, para 14, 19, 20, 21, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G20/095/28/PDF/G2009528.pdf?OpenElement.

- CESCR, Statement on affordable universal vaccination against coronavirus disease (COVID-19), international cooperation and intellectual property, E/C.12/2021/1, para 1, 2, 4; https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3921880?ln=en.

- CESCR, Statement on universal and equitable access to vaccines COVID-19, E/C.12/2020/2, para 1, 2, 3, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3897801?ln=en.

- David Lim & Darius Tahir, Pharmacies’ starring role in vaccine push could create unequal access, POLITICO (December. 18, 2021, 03:20 PM), https://www.politico.com/news/2020/12/18/pharmacies-vaccine-push-unequal-access-448478.

- HRC, General Comment No.10: Non-discrimination, para 2, 10, 13, https://www.refworld.org/docid/453883fa8.html.

- Karen McVeigh, Rich countries leaving rest of the world behind on Covid vaccines, warns Gates Foundation, THE GUARDIAN (December. 10, 2021, 9:40 AM), https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/dec/10/rich-countries-leaving-rest-of-the-world-behind-on-covid-vaccines-warns-gates-foundation;

- Law on Medical Examination and Treatment 2009.

- Law on Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases 2007.

- Lisa Forman & Jillian Clare Kohler, Global health and human rights in the time of COVID-19: Response, restrictions, and legitimacy, 19:5JOURNAL OF HUMAN RIGHTS, 547, 550 (2020), DOI: 10.1080/14754835.2020.1818556.

- 14. NA, Benefits of Getting a COVID-19 Vaccine, CDC (December. 16, 2021, 9:40 AM),https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/vaccine-benefits.html.

- NA, British pilot patient: like a miracle in medicine (Bệnhnhân phi côngngười Anh: nhưmộtkìtíchtrong Y khoa), GENERAL DEPARTMENT OF PREVENTIVE MEDICINE ONLINE (December. 25, 2021, 10:15AM), <https://vncdc.gov.vn/benh-nhan-phi-cong-nguoi-anh-nhu-mot-ky-tich-trong-y-khoa-nd15775.html>.

- NA, Establishing Covid-19 intensive care centers in Ho Chi Minh City: “miracle” from tireless efforts (Thành lậpcáctrungtâmhồisứctíchcực Covid-19 tại TP HCM: “phépmàu” từnhữngnỗlựckhôngmệtmỏi), MINISTRY OF HEALTH PORTAL (December. 25, 2021, 11:00 AM), https://moh.gov.vn/hoat-dong-cua-lanh-dao-bo/-/asset_publisher/TW6LTp1ZtwaN/content/thanh-lap-cac-trung-tam-hoi-suc-tich-cuc-covid-19-tai-tp-hcm-phep-mau-tu-nhung-no-luc-khong-met-moi.

- Son Dao Xuan, Abolition of intellectual property rights for Covid-19 vaccines: conflicts between public health and the TRIPS Agreement (Bãibỏquyềnsởhữutrítuệđốivới vaccine Covid-19: mâuthuẫngiữasứckhoẻcộngđồngvàHiệpđịnh TRIPS), VIETNAM LAW JOURNAL (December. 6, 2021, 05:20 PM), https://lsvn.vn/bai-bo-quyen-so-huu-tri-tue-doi-voi-vaccine-covid-19-mau-thuan-giua-suc-khoe-cong-dong-va-hiep-dinh-trips1622996956.html.

- Thang Huy, Fund will be established for public-private cooperation in the purchase of COVID-19 vaccine (SẽlậpQuỹđểhợptáccông-tưtrongviệcmua vaccine COVID-19), MINISTRY OF HEALTH PORTAL(December.28, 2021, 02:20 PM), https://moh.gov.vn/hoat-dong-cua-dia-phuong/-/asset_publisher/gHbla8vOQDuS/content/se-lap-quy-e-hop-tac-cong-tu-trong-viec-mua-vaccine-covid-19?inheritRedirect=false.

- The Covid-19 vaccine fund was established under the Prime Minister’s Decision No. 779/QD-TTg dated May 26, 2021.

- Van Ha, Prime Minister launches the largest vaccination campaign in history for 75 million people in Vietnam (Thủtướngphátđộngchiếndịchtiêmchủnglớnnhấtlịchsửcho 75 triệungườidân Việt Nam), MINISTRY OF HEALTH PORTAL (December. 25, 2021, 11:17 AM), https://moh.gov.vn/hoat-dong-cua-lanh-dao-bo/-/asset_publisher/TW6LTp1ZtwaN/content/thu-tuong-phat-ong-chien-dich-tiem-chung-lon-nhat-lich-su-cho-75-trieu-nguoi-dan-viet-nam.

Cite this article as:

Dr. Nguyen Thi Hong Yen & Ms. Tran Thi Thu Thuy, “Ensuring The Right To Access Vaccine of Citizens During The Covid-19 Pandemic: Experiences From Vietnam”, Vol.3 & Issue 3, Law Audience Journal (e-ISSN: 2581-6705), Pages 321 to 342 (7th February 2022), available at https://www.lawaudience.com/ensuring-the-right-to-access-vaccine-of-citizens-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-experiences-from-vietnam/.

Footnotes:

[1] Figure at: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations, update February. 5, 2022.

[2] Figure at:https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/, update February. 5, 2022.

[3] NA,Benefits of Getting a COVID-19 Vaccine, CDC (December. 16, 2021, 9:40 AM),https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/vaccine-benefits.html.

[4] Our World in Data is a project of the Global Change Data Lab, a non-profit organization based in the United Kingdom. Our World in Data is produced as a collaborative effort between researchers at the University of Oxford, who are the scientific contributors of the website content; and the non-profit organization Global Change Data Lab, who owns, publishes and maintains the website and the data tools.

[5] Figure at:https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations#what-share-of-the-population-has-received-at-least-one-dose-of-the-covid-19-vaccine.

[6] Figure at:https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations#what-share-of-the-population-has-received-at-least-one-dose-of-the-covid-19-vaccine.

[7] CESCR, General Comment No. 14: The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health (Art. 12), E/C.12/2000/4, para.16, https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/4538838d0.pdf.

[8]Ibid, para. 9.

[9]CESCR, Statement on the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic and economic, social and cultural rights, E/C.12/2021/1, para 14, 19, 20,21, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G20/095/28/PDF/G2009528.pdf?OpenElement.

[10]CESCR, Statement on universal and equitable access to vaccines COVID-19, E/C.12/2020/2, para 1, 2, 3, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3897801?ln=en.

[11]Ibid, Para 4.

[12]Ibid, Para 5.

[13]HRC, General Comment No.10: Non-discrimination, para 2, 10, 13, https://www.refworld.org/docid/453883fa8.html.

[14] Clause 1, Article 3 of the Law on Medical Examination and Treatment 2009.

[15]Article 5 Law on Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases 2007.

[16] NA, British pilot patient: like a miracle in medicine (Bệnhnhân phi côngngười Anh: nhưmộtkìtíchtrong Y khoa), GENERAL DEPARTMENT OF PREVENTIVE MEDICINE ONLINE(December. 25, 2021, 10:15AM), <https://vncdc.gov.vn/benh-nhan-phi-cong-nguoi-anh-nhu-mot-ky-tich-trong-y-khoa-nd15775.html>.

[17] NA, Establishing Covid-19 intensive care centers in Ho Chi Minh City: “miracle” from tireless efforts (Thành lậpcáctrungtâmhồisứctíchcực Covid-19 tại TP HCM: “phépmàu” từnhữngnỗlựckhôngmệtmỏi), MINISTRY OF HEALTH PORTAL (December. 25, 2021, 11:00 AM), https://moh.gov.vn/hoat-dong-cua-lanh-dao-bo/-/asset_publisher/TW6LTp1ZtwaN/content/thanh-lap-cac-trung-tam-hoi-suc-tich-cuc-covid-19-tai-tp-hcm-phep-mau-tu-nhung-no-luc-khong-met-moi.

[18] Binh Thai, Who are the 11 groups of subjects who are vaccinated against COVID-19 in Vietnam? (11 nhómđốitượngđượctiêmvắcxinphòng COVID-19 tại Việt Nam gồmnhững ai?, PORTAL OF THE MINISTRY OF HEALTH ABOUT COVID-19 PANDEMIC(December. 25, 2021, 11:15 AM),https://ncov.moh.gov.vn/en/-/6847426-1677.

[19]Van Ha, Prime Minister launches the largest vaccination campaign in history for 75 million people in Vietnam (Thủtướngphátđộngchiếndịchtiêmchủnglớnnhấtlịchsửcho 75 triệungườidân Việt Nam),MINISTRY OF HEALTH PORTAL(December. 25, 2021, 11:17 AM), https://moh.gov.vn/hoat-dong-cua-lanh-dao-bo/-/asset_publisher/TW6LTp1ZtwaN/content/thu-tuong-phat-ong-chien-dich-tiem-chung-lon-nhat-lich-su-cho-75-trieu-nguoi-dan-viet-nam.

[20] Figure at: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations.

[21]Figure at: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations.

[22]CESCR, Statement on universal affordable vaccination against coronavirus disease (COVID-19), international cooperation and intellectual property, E/C.12/2021/1, para 1, 2, 4; https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3921880?ln=en.

[23]Lisa Forman & Jillian Clare Kohler,Global health and human rights in the time of COVID-19: Response, restrictions, and legitimacy, 19:5JOURNAL OF HUMAN RIGHTS, 547, 550 (2020), DOI: 10.1080/14754835.2020.1818556.

[24] Karen McVeigh, Rich countries leaving rest of the world behind on Covid vaccines, warns Gates Foundation, THE GUARDIAN (December. 10, 2021, 9:40 AM), https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/dec/10/rich-countries-leaving-rest-of-the-world-behind-on-covid-vaccines-warns-gates-foundation; David Lim & Darius Tahir,Pharmacies’ starring role in vaccine push could create unequal access, POLITICO (December. 18, 2021, 03:20 PM), https://www.politico.com/news/2020/12/18/pharmacies-vaccine-push-unequal-access-448478.

[25] SonDao Xuan, Abolition of intellectual property rights for Covid-19 vaccines: conflicts between public health and the TRIPS Agreement (Bãibỏquyềnsởhữutrítuệđốivới vaccine Covid-19: mâuthuẫngiữasứckhoẻcộngđồngvàHiệpđịnh TRIPS),VIETNAM LAW JOURNAL(December. 6, 2021, 05:20 PM), https://lsvn.vn/bai-bo-quyen-so-huu-tri-tue-doi-voi-vaccine-covid-19-mau-thuan-giua-suc-khoe-cong-dong-va-hiep-dinh-trips1622996956.html.

[26]Thang Huy, Fund will be established for public-private cooperation in the purchase of COVID-19 vaccine (SẽlậpQuỹđểhợptáccông-tưtrongviệcmua vaccine COVID-19),MINISTRY OF HEALTH PORTAL(December.28, 2021, 02:20 PM),https://moh.gov.vn/hoat-dong-cua-dia-phuong/-/asset_publisher/gHbla8vOQDuS/content/se-lap-quy-e-hop-tac-cong-tu-trong-viec-mua-vaccine-covid-19?inheritRedirect=false.

[27] The Covid-19 vaccine fund was established under the Prime Minister’s Decision No. 779/QD-TTg dated May 26, 2021.

[28] Figure at: https://quyvacxincovid19.gov.vn/.

[29]BT, Vietnam’s success in the biggest vaccination campaign in history (Thành côngcủa Việt Nam trongchiếndịchtiêmchủnglớnnhấtlịchsử), SOCIALIS REPUBLIC OF VIET NAM, GOVERNMENT NEWS (January. 5 2022, 04:05 PM), https://baochinhphu.vn/thanh-cong-cua-viet-nam-trong-chien-dich-tiem-chung-lon-nhat-lich-su-102306509.htm.